In 1991, Darla Davenport-Powell created a doll and named her Niya in the full awareness of the influence that dolls have on African American children who play with them. Such is the toy’s significance that in the 1940s, African American sociologists Drs. Kenneth and Mamie Clark chose the doll when they conducted a test to determine the psychological effects of segregation on African American and white children.

Davenport-Powell joins a chorus of enterprising African American doll makers whose models of toy culture renew the spirit of childhood playtime and, more important, child advocacy. In this spirit, Davenport-Powell is a keeper of the doll making tradition as practiced by men and women throughout history: from the crude designs crafted by slave mothers to the papier-mâché dolls with the signature teardrop handmade by 19th century black doll maker Leo Moss.

When Davenport-Powell designed Niya, a dynamic multi-lingual doll, her creation made a place for her on the continuum of African American artistic expression. The doll maker connects with her contemporary African American doll makers, whose dolls nourish self-esteem, self-pride, and self-acceptance, including the cloth and vinyl creations by Patricia Green; the sophisticated designs of VonZetta Gant and Daisy Carr; the soft-sculptures of Patricia Coleman Cobb; the expressions of Mari Morris; and, the lush extravagant vision of Byron Lars. As are her current toy “siblings,” Niya is a doll that fosters diversity; her make and style attract collectors, parents, and children from across lines of race and ethnicity. As Niya says on her website Niyakids.com, she “spreads the message of love and cultural awareness through music, songs and languages [and] is today’s multi-cultural voice celebrating the magic of children across the globe.”

… all children deserve to see themselves in the books they read, the toys they play with, and on they shows they watch.

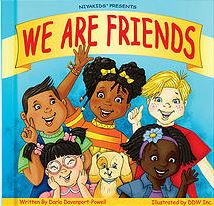

The Niya doll generated a robust interest through mail order, specialty shops, and trade shows. This interest led her creator to seek wider distribution. As a result, ABC’s American Inventor chose Davenport-Powell as a contestant during its 2005-2006 season; she was one of the 12 finalists who received $50,000 to advance their product to the next level. Davenport-Powell, however, did not stop at imagining Niya, the doll; in addition, she has written two children’s books, Here Comes Niya! and her latest, entitled We Are Friends, Niya’s community of interracial playmates and produced its audiobook.

I interviewed Davenport-Powell, and spoke with her about the importance of producing African American artistic cultural artifacts that uplift our children during playtime. Of particular note, we talked about her desire to move into the genre of literature and the audiobook to spread Niya’s message of diversity.

Why literature?

Early on I had books that opened up the world to me and allowed me to travel outside of the confines of (my hometown) Columbia, South Carolina. I would daydream about being in different places with different people in different time periods. Books allowed me to go beyond what society expected of a little black girl. I placed myself in the fiction that I read.

What was the one children’s book that really inspired you to dream and to move beyond communal boundaries?

The Little Engine That Could was my favorite. I identified with that “Little Engine” because there was something about the power of belief that resonated with me. I was encouraged early on by my parents and the people in my community to believe in myself and to be persistent in achieving my goals. I can remember repeating, “I think I can! I think I can! I think I can!” when facing many challenges.

We are familiar with the Dick and Jane books, a line of children’s literature used to teach children how to read from the 1930s through the 1970s. In the 1960s, Richard Wiley included the African American family in the series. How does We Are Friends follow in this tradition of teachable texts?

The very basic concept is about accepting one’s self (flaws and all) and celebrating the differences in others. We Are Friends teaches children and adults about the beauty of acceptance, diversity and inclusion. The book is dedicated to children who have been bullied, teased or called names. It’s like Dick and Jane in that the structure is short and simple.

Niya and her Friends model healthy self-acceptance and convey to the world the value of diversity–which is about embracing differences and similarities.

So in what ways does the We Are Friends picture book differ?

The Dick and Jane books that I read as a child did not have friends that looked like myself. I felt left out, and lost interest very quickly. The We Are Friends picture book features a rainbow of characters of different races, ethnicities, learning styles, cultures, gender and special needs. It’s a book where children can see the humanity in characters that don’t look, talk, act, learn or think as they do. It is a lesson for adults as well.

So some children’s literature you found lacking. Were there any images on television that did not fit the bill?

Yes, absolutely. I remember the excitement of waking up early Saturday morning to watch my favorite cartoons and kid shows—Captain Kangaroo, Kukla, Fran & Ollie, Mr. Rodgers, Shari Lewis & Lamb Chop, the Mickey Mouse Club, Romper Room and others. At the end of Romper Room, for instance, I became very sad. Miss Nancy would look through her magic mirror and never call my name. Each Saturday I would sit in front of the television hoping to hear my name. I felt invisible. That made an imprint on my life, and I vowed to change the game when I became an adult. That’s why on the last page of the We Are Friends book, Niya stretches out her hand with a mirror attended by the words “and the only friend missing is you!”

As a community, what exactly does Niya and her Friends convey to the listeners, readers, and children who play with the dolls?

Niya and her Friends model healthy self-acceptance and convey to the world the value of diversity—which is about embracing differences and similarities. The book, We Are Friends encourages children to learn, to grow, and to live together. It teaches them to accept their unique individuality and to be comfortable in the skin that they are in, flaws and all. It’s a challenge because we live in a society that generally does not tolerate those who do not fit its created “norm.” Niya and her friends are tools to help children to be proud of who they are and to understand, that which makes them different, makes them special.

Can children do this by themselves?

No! Dr. Dorothy Law Nolte, says it best in her poem, “Children Learn What They Live”: If children live with hostility, they learn to fight / If children live with acceptance, they learn to love / If children live with approval, they learn to like themselves”. Adults are conduits for teaching children respect, love, acceptance and everything else they learn—positive and negative.

You dedicate We Are Friends to “every child who has been bullied, teased or called names” yet, there are no instances of bullying in the text. In what ways would Niya and her friends handle bullying?

Bullying is not present in the storyline because my main focus is on the positive interaction between children. I so believe in that. The book, the characters, the audiobook project present a world that showcases collaboration in the production of positive and joyful outcomes. It says to the child who bullies, “I don’t have to do that because just like my classmates, I have my differences too and I want people to accept me for who I am.” So there are visuals that this particular kid notices, and he or she can figure out that Niya and her friends are not threatened by each other. They communicate, play together, work together, and have fun. The story is well illustrated.

We Are Friends encourages children to … accept their unique individuality and to be comfortable in the skin that they are in, flaws and all.

Talk about the illustrator. Every child is drawn as happy and vibrant beings.

The illustrations were done by Dynamic Designworks, Inc., the same company that designed the Niya and Friend prototypes that were on the ABC American Inventor show. The team created the illustrations from the dolls. Niya and her friends are our children, literally. It was shared midway through the project that the artist who did a great deal of work on our special needs character ‘Jake’ infused her own experience into the illustration. Her son Jake has a disability and lives life in a wheelchair. These characters are real!

I noticed while reading the book that there are no Native American nor Jewish children in Niya’s community of friends—just Asian, Caucasian, Latino, and African.

Stay tuned! We Are Friends is the first offering in the series. New friends will be introduced in the books to come. Our Native American character, Alopay will move into the neighborhood along with others. As Niya travels, she will meet new pals all around the world and her family of friends will expand. This is just the beginning.

What are some of your final thoughts?

First of all, thank you for the opportunity to share my passion and life’s work with your audience. I wish to leave readers with my belief that all children deserve to see themselves in the books they read, the toys they play with, and on they shows they watch. I want children to know that they matter and have value, and that their power is in being an ‘original’ and not a ‘carbon copy’. I want children to become voracious readers and to dream beyond boundaries—knowing that the sky has no limit.

Darla Davenport-Powell is a native of Columbia, S.C. where she and her husband currently reside. She is the founder of the I AM ENUF Foundation, a non-profit mentoring organization that equips youth with leadership skills and tools that foster positive identity development. She is presently developing a Niya and Friends animated cartoon and will soon launch a Kickstarter campaign to raise funds to manufacture the Niya dolls. For more information on the Niya project, visit niyakids.com or contact Darla Davenport-Powell at Greaterworksllc@gmail.com.’Like’ Niya on facebook.com/niyakids or tweet us @niyakids.com.

Notes:

For full article of Darla Davenport-Powell and American Inventor go to: tinyurl.com/86fp9d8.

For more Information on The Clarks and their Dolls Test go to: Interview with Dr. Kenneth Clark, conducted by Blackside, Inc. on November 4, 1985, for Eyes on the Prize: America’s Civil Rights Years (1954-1965). Washington University Libraries, Film and Media Archive, Henry Hampton Collection. These transcripts contain material that did not appear in the final program. Only text appearing in bold italics was used in the final version of Eyes on the Prize.